Adenosine receptors may hasten inflammatory responses to tau pathology, according to a paper published this month in Brain. Researchers led by David Blum of the University of Lille, France, reported that in a mouse model of tauopathy, the adenosine-2A receptors exacerbated tau phosphorylation and memory loss. Though the researchers overexpressed the receptors in neurons, the A2ARs triggered a response in microglia, namely an uptick in inflammatory genes, including the complement protein C1q that has been linked to synaptic pruning in this tauopathy models. The researchers also found more A2A receptors in brains of people who had died with frontotemporal dementia than in healthy controls.

- Adenosine-2A receptor overexpression in a tau mouse model hastened memory loss and synaptic damage.

- People with FTD had more A2A receptors in the frontal cortex.

- The receptors upped expression of microglial genes TREM2 and C1q.

Best known for binding caffeine, adenosine receptors—of which A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 varieties exist—have been implicated in multiple types of neurodegeneration (for review, see Cunha, 2016). Blum’s group previously reported that deleting or blocking the A2A receptor lessened tau hyperphosphorylation and neuroinflammation, spared synaptic function, and rescued memory deficits in Thy-Tau22 mice, which express the P301S mutant form of human tau (Laurent et al., 2014).

Subsequently, the scientists blocked the receptor in APP/PS1 mice and found less amyloid and memory loss (Faivre et al., 2018). Other groups deleted A2AR in astrocytes in both normal and AD model mice and reported improved memory (Dec 2014 news; Jan 2015 news). In humans, brain adenosine receptors reportedly rise with age, and more so in people with AD (Temido-Ferreira et al., 2018).

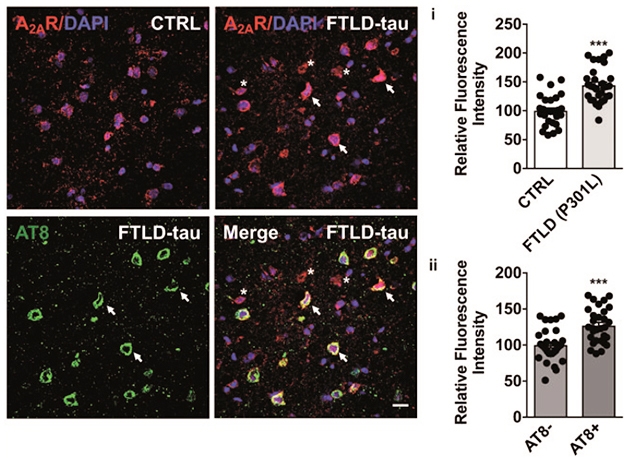

In the current study, first author Kevin Carvalho and colleagues asked if adenosine receptor expression might crank up in a pure tauopathy. Indeed, according to western blots, they found around twice as much A2AR protein in brain extracts from three people with frontotemporal dementia who carried the P301L mutation, than in extracts from three age-matched controls. Immunostaining tissue sections revealed about 25 percent more A2AR in neurons burdened with tau pathology than in those without (see image below).

A2AR in FTD. Immunohistochemistry (left) indicated more A2AR expression (red) in FTD than in control brains. A2AR levels were higher in neurons with tau pathology (arrows) than in those without (asterisks). Relative fluorescence of A2AR staining is plotted on right. [Courtesy of Carvalho et al., Brain, 2019.]

To examine if this elevated A2AR expression might exacerbate the progression of tauopathy, the researchers generated a mouse model in which they could induce overexpression of A2AR in forebrain neurons, then crossed it to the Thy-Tau22 strain. When the A2AR transgene was overexpressed at around one month of age, spatial memory deficits appeared four to five months later. ThyTau22 mice typically start having memory problems around nine months of age. The authors did not keep any A2AR/Tau22 mice on doxycycline for that long. Turning on A2AR also boosted phosphorylation of hippocampal tau at some residues, but not others. Other regions of the forebrain were not assessed for comparison.

To investigate how A2AR might hasten the memory slide, the researchers measured RNA levels in the hippocampi of 6-month-old mice. At this age, Tau22 or A2AR mice did not differ substantially from controls, but Tau22/A2AR mice did. They had 505 differentially expressed genes, of which 441 were downregulated. Most of those function in RNA metabolism, whereas most of the 64 upregulated genes are involved in immune processes. Of the 64, 54 are annotated in the RNA-seq database developed by the late Ben Barres (Zhang et al., 2014). According to this database, 33 of the genes are microglial. They include Trem2, Csf1r, and the complement protein C1qa. Levels of RNA for C1qb and C1qc, the two other proteins that make up the C1q complex, trended toward higher expression.

Investigating the C1q uptick, the researchers found significantly higher protein levels of the C1q complex in Tau22/A2AR mice, particularly in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus. In keeping with the idea that complement tags synapses for destruction, glutamatergic synapses appeared sparse in this region. In Thy-Tau22 mice with normal A2AR expression, C1q levels rose at 9 months of age, coinciding with the first inkling of synaptic deficits and memory loss.

Looking in human brain samples, the researchers found that A2AR correlated with C1q levels in the frontal cortices of people with P301L FTD, as well as in those without the mutation who had corticobasal syndrome or Pick’s disease, two related tauopathies.

Blum believes that A2AR signaling mediates communication between neurons and glia. Though it is unclear why A2AR expression rises in tauopathies, Blum thinks it somehow trips inflammatory responses in glial cells, including the complement cascade, which erodes synapses and causes memory problems. He suspects the same could be true in multiple neurodegenerative diseases.

“The findings reinforce the idea that there is crosstalk between neuronal functions (e.g. oscillations) and the brain immune system, with potential consequences under pathological conditions,” wrote Marc Aurel Busche and Carlo Sala Frigerio of University College London in a joint comment to Alzforum. Future research should focus on what ramps up A2AR in aging and disease, and how this influences glia. “The study also raises the important question of whether—and how—antagonism of A2A receptors (e.g. through caffeine) could have a disease-modifying effect in patients,” they wrote.

Blum told Alzforum that he has initiated a clinical trial testing caffeine as a treatment for cognitive decline in people with mild to moderate AD. The multicenter, placebo-controlled trial will start enrolling participants in Northern France in January 2020, and will test the efficacy of a 400 mg daily dose of caffeine to curb slippage on the neuropsychological test battery over 30 weeks. All participants will be asked to give up their own caffeine starting six weeks prior to the treatment phase.—Jessica Shugart

Research Models Citations

News Citations

- Do Astrocyte Receptors Go Over the Top in Alzheimer’s?

- Paper Alert: Astrocyte Receptor Could Hinder Memory

Paper Citations

- Cunha RA.

How does adenosine control neuronal dysfunction and neurodegeneration?. J Neurochem. 2016 Dec;139(6):1019-1055. Epub 2016 Aug 16 PubMed. - Laurent C, Burnouf S, Ferry B, Batalha VL, Coelho JE, Baqi Y, Malik E, Mariciniak E, Parrot S, Van der Jeugd A, Faivre E, Flaten V, Ledent C, D’Hooge R, Sergeant N, Hamdane M, Humez S, Müller CE, Lopes LV, Buée L, Blum D.

A2A adenosine receptor deletion is protective in a mouse model of Tauopathy. Mol Psychiatry. 2014 Dec 2; PubMed. - Faivre E, Coelho JE, Zornbach K, Malik E, Baqi Y, Schneider M, Cellai L, Carvalho K, Sebda S, Figeac M, Eddarkaoui S, Caillierez R, Chern Y, Heneka M, Sergeant N, Müller CE, Halle A, Buée L, Lopes LV, Blum D.

Beneficial Effect of a Selective Adenosine A2A Receptor Antagonist in the APPswe/PS1dE9 Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:235. Epub 2018 Jul 12 PubMed. - Temido-Ferreira M, Ferreira DG, Batalha VL, Marques-Morgado I, Coelho JE, Pereira P, Gomes R, Pinto A, Carvalho S, Canas PM, Cuvelier L, Buée-Scherrer V, Faivre E, Baqi Y, Müller CE, Pimentel J, Schiffmann SN, Buée L, Bader M, Outeiro TF, Blum D, Cunha RA, Marie H, Pousinha PA, Lopes LV.

Age-related shift in LTD is dependent on neuronal adenosine A2A receptors interplay with mGluR5 and NMDA receptors. Mol Psychiatry. 2018 Jun 27; PubMed. - Zhang Y, Chen K, Sloan SA, Bennett ML, Scholze AR, O’Keeffe S, Phatnani HP, Guarnieri P, Caneda C, Ruderisch N, Deng S, Liddelow SA, Zhang C, Daneman R, Maniatis T, Barres BA, Wu JQ.

An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2014 Sep 3;34(36):11929-47. PubMed.